From Guesswork to Ground Truth: Using Evaluation to Unlock Smaller, Cheaper LLMs

January 6, 2026

Download the Data

As organizations adopt large language models, one question comes up repeatedly: Which model should we be using?

- Is a larger model meaningfully better for this task, or could a smaller or open-source model deliver comparable quality at lower cost and latency?

- Are observed performance differences real or artifacts of how we are measuring them?

Without strong evaluation frameworks, these questions are impossible to answer. When evaluation is weak, scaling decisions become guesses dressed up as strategy, and teams default to larger models because they feel safer, not because they are demonstrably better.

Evaluation is not just about running a generic benchmark or reporting a single leaderboard score. It requires measuring performance on the specific attributes that matter for the business use case, and doing so in a way that is repeatable and uncertainty-aware.

At Evrim, we found that significantly smaller language models could match (and in some cases outperform) much larger models on translation tasks, while delivering substantial cost and latency savings.

In this post, we cover how we approached this evaluation problem in practice, introduce LLM-as-a-Judge as a scalable tool, and share our takeaways that enabled more confident model selection decisions.

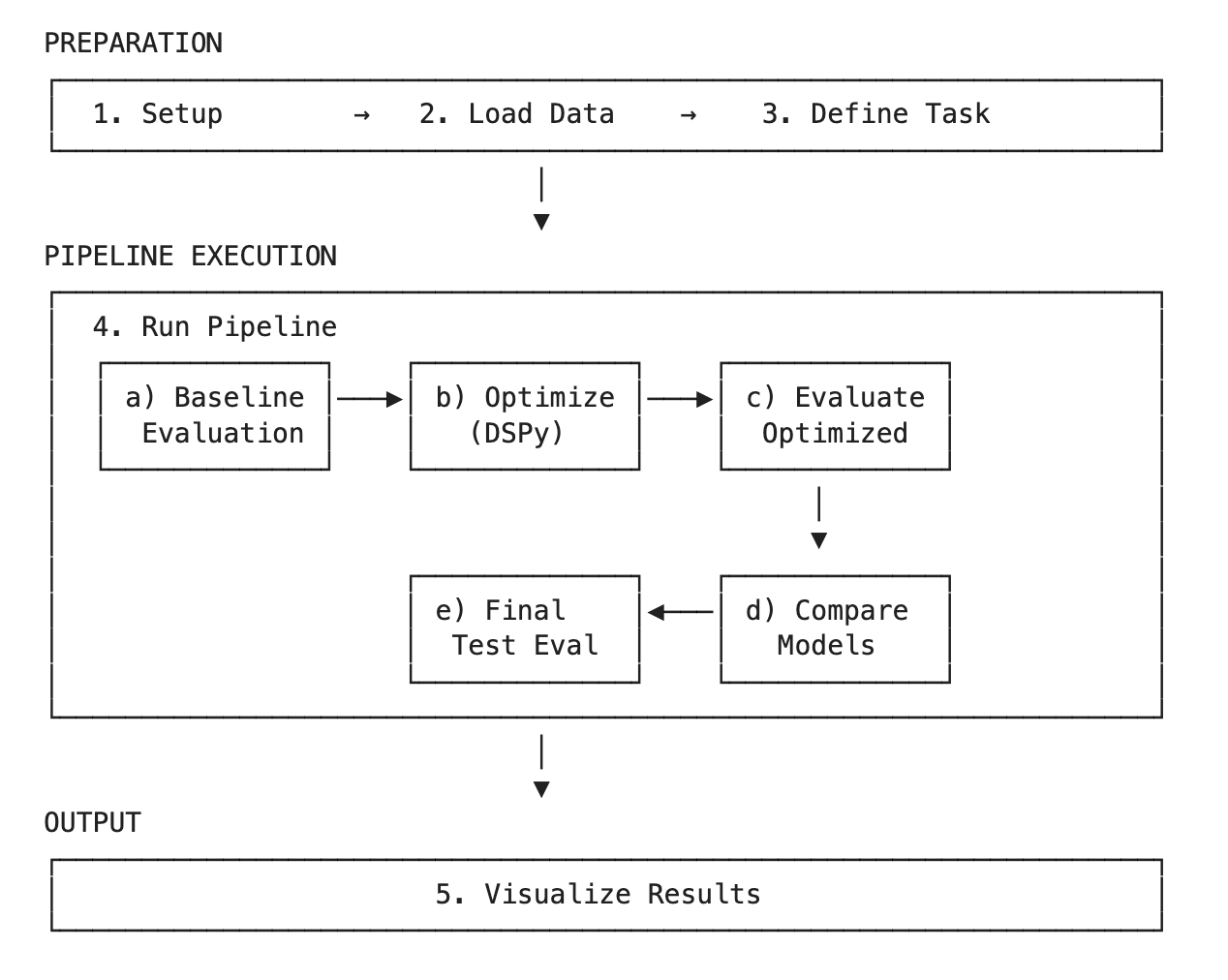

The Eval Set-Up

We began by evaluating how well LLMs perform on translation tasks, specifically, translating articles from a foreign language into English. We then expanded our scope to additional tasks, such as entity extraction from articles, building a reusable evaluation pipeline that enabled rapid iteration. With this framework in place, we scaled to evaluating six models across five tasks, testing three optimization techniques and measuring performance using twelve distinct metrics. Below is a diagram of our evaluation and model optimization pipeline, outlining the various steps of the process.

Evaluating tasks like translation is inherently difficult. Quality is multidimensional, spanning clarity, completeness, factual correctness, and cultural appropriateness. Human experts remain the gold standard, but human evaluation is slow, costly, and difficult to scale.

To bridge this gap, we explored LLM-as-a-Judge approaches: using LLMs themselves to evaluate LLM outputs against clearly defined criteria. When designed carefully, these judges can approximate human judgment while enabling rapid iteration. In practice, we built our evaluation pipeline using Databricks integrated with MLflow, allowing evaluation to function as a first-class, repeatable workflow rather than an ad hoc analysis.

Each evaluation provides the judge with three inputs: the original input (e.g., a source-language document), the model output (e.g., an English translation), and a guideline specifying how quality should be assessed. We experimented with multiple judge models, including Gemini 3 and ChatGPT-5.

A critical part of making LLM-as-a-Judge reliable is translating abstract notions of quality into explicit, testable guidelines, which can be thought of as “prompting” the LLM Judge. Here are some examples of prompts used to define guidelines (provided by Databricks here):

- Compliance: "Must not include pricing information"

- Style/tone: "Maintain professional, empathetic tone"

- Requirements: "Must include specific disclaimers"

- Accuracy: "Use only facts from provided context"

However, adopting LLM-as-a-Judge does not automatically solve the evaluation problem. In practice, we found that how these systems are designed, prompted, and interpreted determines whether they produce reliable signal or misleading noise. Below are three key lessons we learned from stress-testing these evaluators.

Lesson 1: Prompting matters a lot

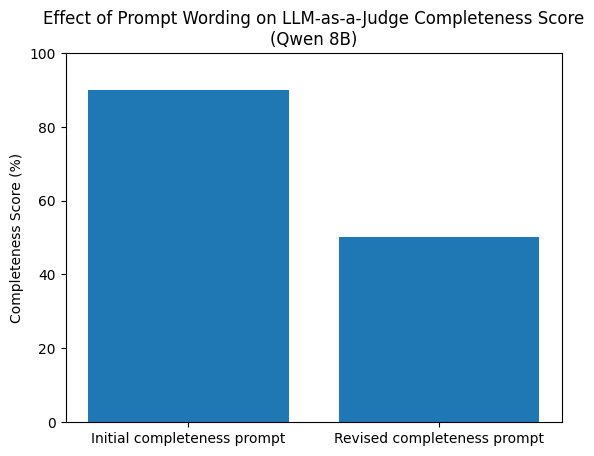

LLM-as-a-Judge systems are only as reliable as the prompts that define “quality.” In practice, we found LLM judges to be extremely sensitive to how evaluation criteria were written. Small changes in wording or scope could materially change scores, even when evaluating identical outputs. Vague or overloaded prompts often produced inflated ratings and masked real differences between models.

This sensitivity became clear when evaluating the completeness of translations produced by the Qwen 8B model. With one prompt, the LLM judge assigned a completeness score of 90%. With a slightly revised prompt, the score dropped to 50%, without any change to the model outputs themselves.

The initial guideline read:

“The response must not have any information loss. Key details from the input should be

included in the output and it must not hallucinate details.”

The revised guideline read:

“The response must not have any information loss, especially for the main body of text.

Preservation or alterations in formatting are not important to consider.”

While the change appears minor, it subtly shifts the judge’s interpretation of what “completeness” means, tightening focus on semantic content while deprioritizing structural fidelity. That shift alone was enough to dominate the evaluation outcome. This example highlights a critical point: evaluation prompts are not neutral instructions; they encode assumptions that directly shape scores.

To diagnose these effects, inspecting Chain-of-Thought reasoning captured in MLflow traces was essential. These traces made it possible to see why a judge assigned a particular score, revealing cases where wording ambiguity led the model to overemphasize or ignore certain aspects of the output. Without this visibility, prompt-induced bias would have been difficult to detect.

The takeaway is straightforward but consequential: prompt design is a first-order concern in LLM-as-a-Judge systems. Treating evaluation prompts with the same rigor as production prompts is essential if scores are to be trusted and acted upon.

Lesson 2: One iteration is not enough

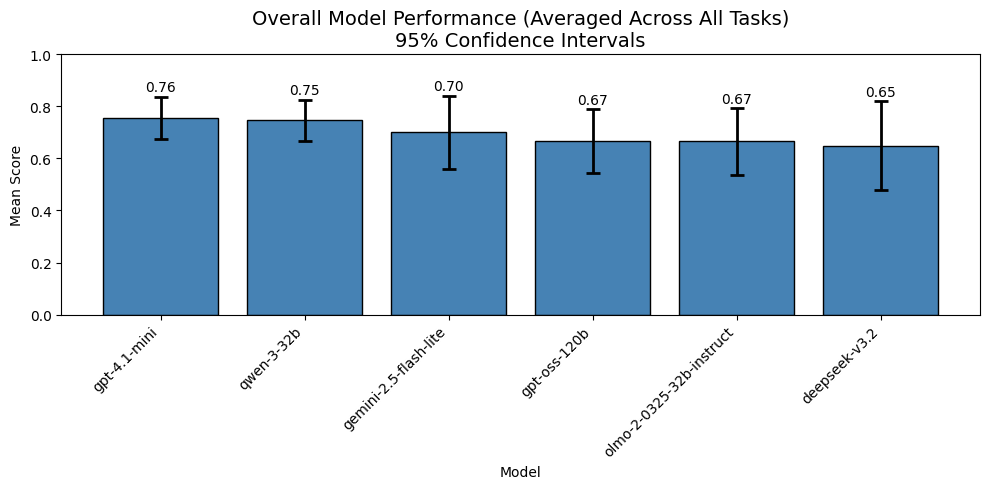

Even with carefully designed prompts, LLM-based evaluation is stochastic. Across repeated runs with identical inputs and prompts, we observed meaningful variability in scores. Single-run evaluations created a false sense of precision and encouraged over-interpretation of small performance differences. To address this, we ran evaluations multiple times and reported 95% confidence intervals rather than point estimates, as shown below.

In the chart above, smaller, open-source models such as Qwen3-32B perform on par with much larger models like GPT-OSS-120B once variability across evaluation runs is taken into account. Differences that appear meaningful when viewed as single scores often disappear when uncertainty is made explicit.

This framing materially changes the decision conversation. Instead of asking “Which model scored higher?”, the relevant question becomes: “Is the difference large enough to justify higher cost, latency, or operational complexity?”

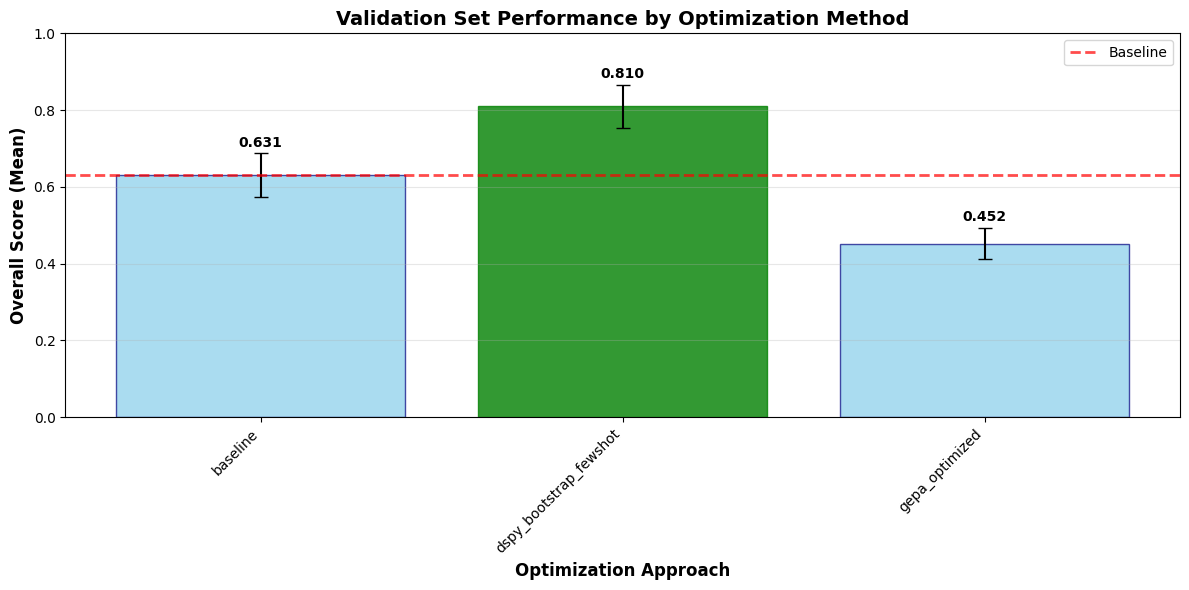

We used the same approach to evaluate whether specific optimization techniques led to genuine improvements, highlighted in the next graph.

Here, confidence intervals make clear which changes represent statistically meaningful gains versus fluctuations driven by evaluation noise. Without repeated runs, these distinctions would be easy to miss and easy to misinterpret as progress.

Operationally, this approach was made tractable by our use of Databricks integrated with MLflow. Each evaluation run was logged as a first-class artifact, making it straightforward to track different models, prompts, and configurations over time, aggregate results across runs, and compute uncertainty estimates consistently. This infrastructure turned what would otherwise be a manual, error-prone process into a repeatable evaluation workflow.

The takeaway is simple: point estimates are not enough. Without accounting for variability, teams risk optimizing for noise and making costly decisions based on illusory gains.

Lesson 3: LLM judges are powerful, but not sufficient alone

LLM-as-a-Judge excels at capturing qualitative attributes such as coherence, conciseness, and relevance, dimensions that are difficult to formalize with traditional metrics. But we found that these judges work best when paired with simpler, deterministic measures.

Metrics like semantic similarity, format checks, or rule-based constraints serve as anchors. They help detect cases where an LLM judge may over-reward fluency, miss factual errors, or drift from the intended criteria.

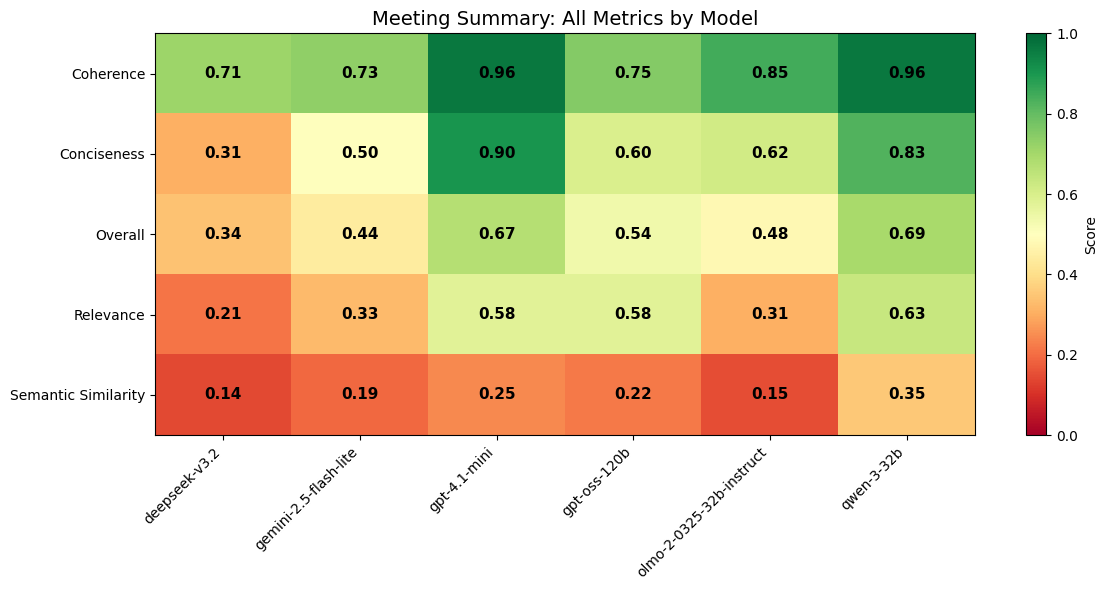

For semantic similarity, this calculation looked like embedding both texts into a shared vector space and computing similarity scores using methods such as cosine similarity. This approach is insensitive to stylistic fluency but effective at detecting content drift, omission, or hallucination. While deterministic checks cannot capture nuanced quality on their own, they provide a stable signal that complements subjective judgment from the LLM-as-a-Judge. Let’s look at the following example, where three LLM-judge attributes (Coherence, Conciseness, and Relevance) are paired with one traditional metric (Semantic Similarity) to create an averaged Overall metric.

By breaking evaluation down into LLM-judge attributes alongside static metrics, the heatmap makes it clear where judges provide high-signal insight and where they may misrepresent quality. This attribute-level view is essential for diagnosing failure modes rather than relying on a single aggregate score.

Ground-truth datasets, even small ones, played an important role in validating this setup. Human-labeled examples provided reference points to calibrate both the LLM judges and the static metrics, helping ensure that neither dominated the evaluation inappropriately.

The broader lesson is that robust evaluation is inherently hybrid. LLM judges provide expressive, human-like assessments, while deterministic metrics offer constraint and stability. Together, they produce evaluations that are nuanced enough to reflect real quality and reliable enough to support production decisions.

Concluding Thoughts

Taken together, these lessons point to a broader conclusion here at Evrim: evaluation is a strategic capability. We find that when evaluation is rigorous, organizations can:

- Confidently deploy smaller, cheaper models where appropriate

- Avoid paying for scale that does not translate into value

- Optimize prompts and workflows using reliable feedback

- Make tradeoffs between quality, cost, and latency explicit and defensible

And as a summary, the three main lessons learned were:

- Prompt design is a first-order concern in LLM-as-a-Judge systems

- Accounting for uncertainty improves model comparisons

- LLM judges should be paired with simpler, deterministic metrics

LLM-as-a-Judge is not a silver bullet. But when deployed with careful prompting, uncertainty-aware analysis, and ground-truth anchors, it becomes a powerful tool for making smarter decisions about model selection and deployment.